We would therefore predict that sodium and lithium have very similar chemistry, which is indeed the case.Īs we continue to build the eight elements of period 3, the 3 s and 3 p orbitals are filled, one electron at a time. It is readily apparent that both sodium and lithium have one s electron in their valence shell.

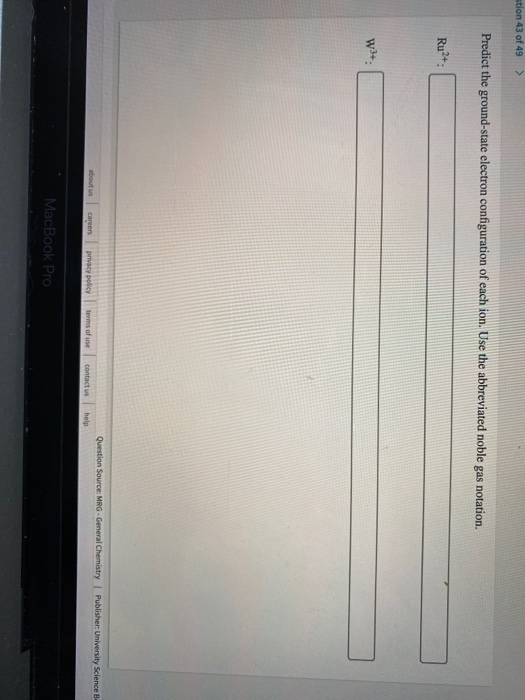

Using this notation to compare the electron configurations of sodium and lithium, we have: Sodium The simplified notation allows us to see the valence-electron configuration more easily. This means that the chemistry of an atom depends mostly on the electrons in its outermost shell, those with the highest n-value, which are called the valence electrons. We will revisit this definition of core electrons later on for transition metals. Thus, the core electrons are those in the atomic orbitals with n < 3, namely those in the 1s, 2s and 2p orbitals. For example, in the sodium atom the highest n-value is 3. For the representative elements (columns 1, 2, and 13-18 of the Periodic Table), the core electrons are all electrons with an n-value lower than the maximum n-value in the electron configuration. For example, represents the 1 s 2 2 s 2 2 p 6 electron configuration of neon ( Z = 10), so the electron configuration of sodium, with Z = 11, which is 1 s 2 2 s 2 2 p 6 3 s 1, is written as 3 s 1Įlectrons in filled inner orbitals are closer to the nucleus and more tightly bound to it, and therefore they are rarely involved in chemical reactions. In practice, chemists simplify the notation by using a bracketed noble gas symbol to represent the configuration of the noble gas from the preceding row because all the orbitals in a noble gas are filled. Figure 2.1.1 tells us that the next lowest energy orbital is 2 s, so the orbital diagram for lithium isĪs we continue through the periodic table in this way, writing the electron configurations of larger and larger atoms, it becomes tedious to keep copying the configurations of the filled inner subshells. We know that the 1 s orbital can hold two of the electrons with their spins paired.

The next element is lithium, with Z = 3 and three electrons in the neutral atom. Otherwise, our configuration would violate the Pauli principle. Written as 1 s 2, where the superscript 2 implies the pairing of spins. The orbital diagram for the helium atom is therefore From the Pauli exclusion principle, we know that an orbital can contain two electrons with opposite spin, so we place the second electron in the same orbital as the first but pointing down, so that the electrons are paired. We place one electron in the orbital that is lowest in energy, the 1 s orbital. Unless there is a reason to show the empty higher energy orbitals, these are often omitted in an orbital diagram: Figure 2.1.1), and the electron configuration is written as 1 s 1 and read as “one-s-one.”Ī neutral helium atom, with an atomic number of 2 ( Z = 2), has two electrons. Some authors express the orbital diagram horizontally (removing the implicit energy axis and the colon symbol): Here is a schematic orbital diagram for a hydrogen atom in its ground state: A filled orbital is indicated by ↑↓, in which the electron spins are said to be paired. We use the orbital energy diagram of Figure 2.1.1, recognizing that each orbital can hold two electrons, one with spin up ↑, corresponding to m s = +½, which is arbitrarily written first, and one with spin down ↓, corresponding to m s = −½. First we determine the number of electrons in the atom then we add electrons one at a time to the lowest-energy orbital available without violating the Pauli principle.

We construct the periodic table by following the aufbau principle (from German, meaning “building up”).

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)